Personal response to GLA/MHCLG consultation on ‘measures to support housebuilding in London’

Michael Edwards, Bartlett School of Planning, UCL, and Just Space, January 2026

sent to londonplan@london.gov.uk and londonhousingconsultation@communities.gov.uk<londonhousingconsultation@communities.gov.uk>

This response…

…is from an experienced scholar of London planning, especially of the economic aspects of housing. I have contributed to group responses sent by Just Space (a network of community activist organisations in London) and the Highbury expert group on national housing supply but this personal response is necessary because the friends and colleagues in these organisations – from whom I have learned so much – are not adequately stressing the benefits of the collapse in speculative housing sales and output.

Key point: celebrate

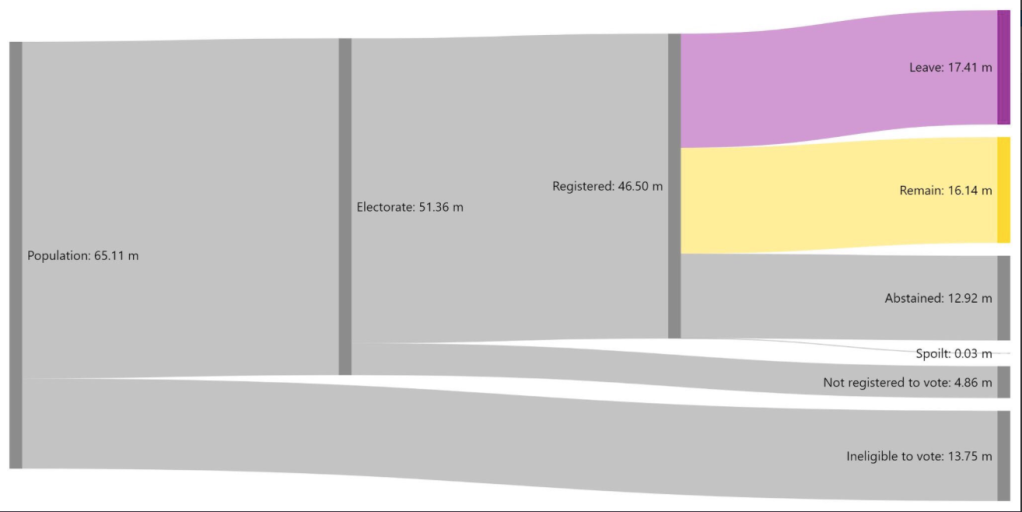

Policymakers at all levels of government in Europe and the UK, down to London boroughs, or most of them, have subscribed to the mistaken belief that the housing affordability crisis is mainly the result of an inadequate supply of housing relative to demand and that the policy solution must be for public policy to boost supply. This leads to weak regulation of private developers and landlords and massive public subsidy to developers and landlords. Housebuilding firms and landed interests invest heavily in promotion of these strategies through think tanks like the Centre for Cities and London business organisations. It is made to seem like common sense and is echoed by GLA research and the London Boroughs. Housing and land price escalation are now key processes in the whole urban system, in family savings strategies, banking stability and the growth of regional disparities. Challenges to the orthodoxy and system-wide analyses are still mainly within the research community.

The London planning and housing system, since at least 2000, has tried to maximise the output of housing rather than doing what was most needed: maximise the stock of council housing which is where the GLA’s own figues show that the need is greatest and the backlog always growing. Not enough council homes are built while much is lost through the Right-to-Buy policy, sell-offs and estate regeneration.

Believers in this strategy have trouble demonstrating where and how the production of housing for market sale helps lower the housing costs facing low income households and homeless people. (With income and wealth inequality now at unprecedented levels it would be remarkable if it worked.) The world’s research literature is scoured for examples but the GLA have to admit that nothing is so effective as direct production of low-rent homes.

At best, the build-build-build strategy in a de-regulated planning environment might lower house prices by a few percentage points if sustained for a decade. But that effect has been swamped by price increases often averaging many times that, year after year. Until recently. The slowdown of sales and new production in London in the last year or two is the first sign that greater affordability may be on the way. Developers, who resist lowering prices if they can, will be driven to do so and will reduce their land holdings, eventually stabilising and even lowering the prices they pay for sites. This should all be welcomed and encouraged.

If public authorities are concerned, as they should be, to avoid permanent damage to housebuilding capacity they can take advantage of falling prices to acquire unsold homes from developers and commission more council homes.

Thus we should celebrate the ‘crisis’ of London housebuilding and adopt thoughtful ways to manage it to – finally – secure the housing London needs.

Futher observations

There will be resistance to this radical approach. The following comments are designed to make the best of a bad job: to avoid making things worse. They draw heavily on the formulations by Michael Ball and the people at Just Space.

Londonhas an entirely unrealistic housing target of 88,000 new homes per annum. Only once have over 80,000 homes been built in a year, in 1933 when most of today’s GLA area was green fields. The average number of new homes built each year, for the past twenty, is 35,000.

Last year panic set in when there were only 2,158 new home starts in the six months to June. In response the government and Mayor announced this set of ‘measures to support housebuilding in London’, which they said ‘…responds to the current challenging macro-economic circumstances and the changing national regulatory landscape which have led to a reduction in housebuilding in the capital’.

But there was no real analysis why speculative housebuilding had come to a juddering halt. Landbanking (300,000 homes permitted but not built) and developer profit (£2bn for top-five housebuilders in 2024-25) went unexamined. So did the flat-lining UK economy which underpins domestic demand; so did people’s loss of confidence in new-build safety and quality and the leasehold system.

Instead, the measures take aim at affordable housing, a long-standing target of the housebuilder lobby, and also at standards for better quality and safer homes, post-Grenfell. The proposals’ centre-piece is a reduction in the affordable housing requirement, with the hope that this will kick-start stalled developments, by making them more profitable. Other changes proposed include reducing cycle parking, permitting more single-aspect flats, and increasing the number of homes served by each building core. Reductions in borough CIL and increasing the Mayor’s powers to decide planning applications are subject to a parallel, government, consultation.

The measures are proposed to be time-limited, up to 31 March 2028 (or the adoption of a new London Plan, whichever is sooner), but changes made now for new developments cannot be undone. Clearly the GLA’s hope is that developers will take speedy advantage of the changes and hasten to get permissions and commence a surge of schemes. Architect Tom Young points out that many investors and developers, seeing a policy retreat, may hold on in the expectation of yet further retreats, testing how far governments and planning authorities will go to support development profitability.[i] We should also expect many developers who hold permissions based on 35% or better ‘affordable’ housing proportions to re-submit for new permissions with lower percentages and make a start (perhaps just digging a trench) before these new permissions expire.

The comments below follows the order of the consultation.

Cycle Parking

The Mayor’s London Plan requires a certain amount of cycle parking from new developments, according to how many larger homes there are. The proposal is to reduce this from 2 spaces per larger home to 1.2 – 1.9 spaces. London’s boroughs are also being divided into 3 tiers, with developments in some boroughs having to provide less cycle parking than others. Some of the private development parking provision may also be sited on public land (i.e. pavements or the highway).

Objections

- No evidence is provided that this will make any great difference to scheme profitability.

- The physical impact will be on our already crowded pavement and streets.

- No mention is made of the reason for existing cycle parking standards: to enable and encourage their use, to reduce reliance on the car, to create healthy streets

Dual Aspect flats

The Mayor requiresnew homes to be dual aspect, unless this is exceptionally difficult. The current (2021) policy was a hard-fought compromise in the 2019 Examination in Public. The proposal is to remove this requirement.

Objections

- Dual aspect flats are better ventilated, give more light and ventilation so are happier places to live in than single aspect flats: better able to cope with overheating in summer and to ventilate against condensation and mould year-round.

- There is no evidence from the Mayor of how much removing dual aspect will improve scheme profitability.

Number of flats per core

The Mayor requires no more than 8 flats per floor of each core. The proposal is to remove this limit.

Objections

- This change raises safety concerns. No upper limit of flats has been proposed.

- The number of flats should not depend solely on fire safety regulations about distances from flats to core exits.

Affordable Housing

TheMayor now requires 35% of housing to be ‘affordable,’ with 50% required for developments on public land. The proposal is to reduce this to 20% ‘affordable’ housing for private land developments, with 35% on public land, (of which 60% social rent in both cases).

Objections

- Developers will still be able to give less affordable housing, if they can justify it with a viability assessment

- The clear need is for the most ‘affordable’ housing, especially social rented housing; these proposed measures would give us more (unaffordable) market housing instead, when the demand for this has collapsed.

- The Mayor does not show, with evidence, how these measures will work in practice and makes no estimate of how many homes or affordable homes they will provide.

- The proposals do not address other factors such as increased build and labour costs, a sluggish national economy, distrust of safety and quality standards; the whole burden of improving profitability falls on affordable housing.

- The Mayor does not consider whether developers’ profit levels at 15%-20% of Gross Development Value are too high.

- These proposals will not speed up delivery of completed new homes, just their start. Developers will be able to wait until the market improves, before completing the homes, cashing in on the ‘emergency measures’.

- If these measures were to ‘succeed’ it would mean four out five homes would be unaffordable market homes beyond the means of most Londoners.

- Reducing the ‘affordable’ housing in developments could increase land values, making viability problems worse when the priority should be bringing land values down through density controls and other measures.

- Developments with high levels of market housing and low ‘affordable’ housing can often increase local prices and rents and displace local people.

- The massive carbon footprint of housing developments demands that they should provide housing affordable to most people, not housing that cannot be afforded.

Grant funding

Schemes thatoffer the new lower levels of ‘affordable’ housing will be eligible for grants of between £70,000 and £220,000 per affordable home, beyond the first 10% of affordable housing, with the most grant for social rented housing.

Objections

- Grants, along with CIL relief, would be better spent improving the viability of schemes and maintaining the present level of 35% and 50% affordable housing.

Viability reviews These are used to ensure schemes do not make extra profit at the expense of affordable housing. They should guarantee that super-profits (beyond 20%) are used for additional affordable housing. The proposal is that there is no review of schemes if the first floor has been built by 31 March 2030. Otherwise there will be a late review once 75% of homes are occupied.

- The viability reviews that are supposed to make sure that developers speed up delivery are even weaker than those in force at the moment.

- The proposed reviews allow the developer to keep too much of any extra profit

- Viability reviews are essential, there must be early and late stage reviews with additional profit going towards additional affordable housing

- The reviews will not speed up delivery of completed new homes, just their start.

Conclusion on the London Plan prospects.

For some time it has been clear that City Hall knows that low rent housing. is what matters most and has been hemmed in by conservative national governments insistence on the maximsiation of total outputs. The new Labour government has adopted the previous government’s approach to an extreme degree. The Mayor already has an evidence-based response to himself in the form of the Greater London Authority’s own submission of July 2025 to the Government on Planning Reform Working Paper ‘Speeding Up Build Out’, which contradicts the rationale behind these proposed emergency measures. These July pproposals are explained by Robin Brown in his submission and I am indebted to him for the insight. [ https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/planning/who-we-work/working-government/mayoral-responses-government-consultations ]

I strongly support Mr Brown’s comments on the MHCLG components of this consultation:

CIL Relief:Removing up to 80% of Borough CIL is a direct attack on local infrastructure funding. The GLA emphasises infrastructure’s role in enabling development; this measure sabotages it. It will subsidise developer profits and inflate land values without a guaranteed increase in housing supply or affordability.

Expansion of Mayoral call-in powers:

Democratic local decision-making is essential for legitimacy and place-making. Extending call-in powers to smaller sites (50+ homes) and Green Belt/MOL sites centralises power and threatens local oversight, enabling inappropriate development against community wishes.

[i] The concessions proposed by the Mayor now have a remarkable similarity to the list of concessions which the Homebuilders Federation (HBF) sought in their response last autumn to the Mayor’s Towards a New London Plan.

Thanks to all those who commented on yesterday’s draft. The consultation responses of Just Space and some others are listed and can be downloaded from Just Space. I’m struck by the fact that the Homebuilders Federation (James Stephens) effectively responds by welcoming the proposals but saying that housing developers need even more government support.