This post, which will be written over some days or weeks, is my notes as I read A City for All Londoners, published in late October 2016 as the Mayor of London’s first airing of the policies and approaches he has in mind as the basis for the new London Plan, a draft of which is expected in the autumn of 2017. Previous mayors, so far as I recall, have called their equivalents ‘Towards a London Plan’.

What I write here is personal, not the views of Just Space, nor of UCL, nor of the Queen of England. In the back of my mind as I read are the Community-led Plan for London documents which Just Space has been working on for 18 months and in which I have played a small supporting role, mainly on economy.

The first comment I have is on the format. There are no printed copies available, I gather, so everyone must use the PDF. The version the GLA posted was over-designed and terribly unfit for purpose. At first sight it looked like a layout for a 96 page saddle-stitched A5 booklet. But the PDF was compiled so it prints 2-up on landscape A4 and it’s tricky to print so the pages are all the right way up. How many low- and middle-income and/or elderly Londoners have the skill and equipment to print things like this or could pay to get it done on the high street or at the library?

Many will want to (or have to) read it on screen, and for that it was deeply unsuitable, mainly because the text is in narrow columns, between 2 and 4 to a page. One has to scroll up and down, left to right to read it: impossibly burdensome, especially on a phone. Nobody seems to have been thinking and I wrote to GLA asking them for a user-friendly version. Meanwhile here is a smaller version which is better for scrolling on devices. city_for_all_londoners_small though the resolution is bad on the maps. Success: within a couple of days Ben Johnson, the mayor’s advisor on Digital matters replied to say that the team had replaced the bad PDF with a better one. The new one scrolls in the same simple way as our version and his high resolution images (though the page numbers no longer correspond). Congratulations to them for listening. And they say they are giving thought to improving the accessibility of documents in future, especially consultation documents.

My wry friend Robin, when we first looked at it, came to a page with a map and said “Oh look, no photo of the mayor.” He was spot on: this plan has something like 20 photos of the mayor. That must a world class achievement. A professor I know carefully deleted all these pictures of the mayor to conserve his ink cartridges: it’s not just the poor who economise.

The mayor’s foreword is warm and personal, emphasising his fear that young Londoners today are being deprived of the opportunities he had. The strains of growth are referred to, but the growth itself is unquestioned.

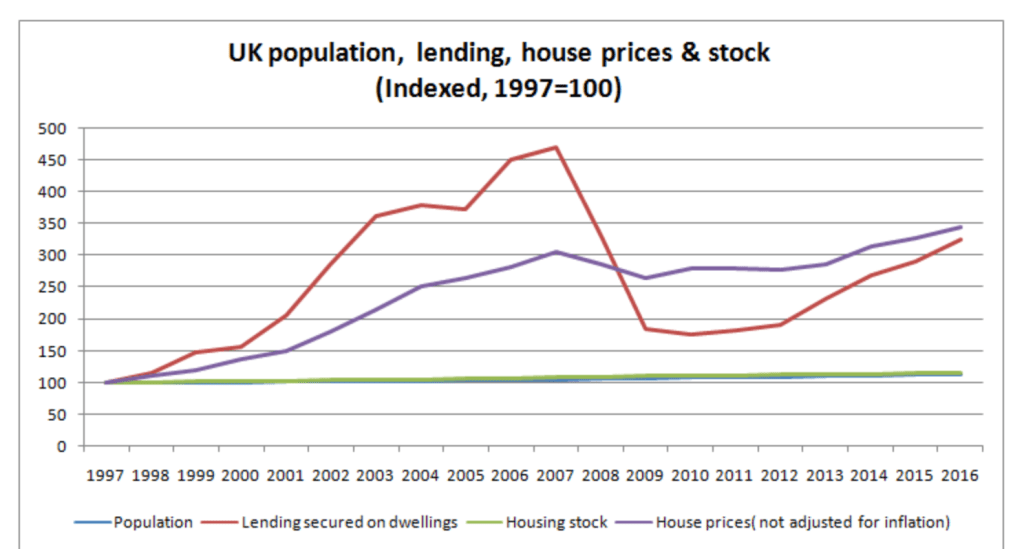

The summary and structure are simple and make clear the thrust. First comes Accommodating Growth. No questioning the desirability or the character of growth, or the ambition to fit as much as possible of it within London – a slight shift from previous mayors who pretended it could all be fitted in. Housing is, as usual, treated just as a supply problem (not enough have been built, and so on) without any reference to how demand got so out of hand, so inflated, so unequal. Nothing about the haemorrhaging of the social housing stock and no attempt to qualify his use of the word ‘affordable’. No mention at all of private renting or of cuts and caps to benefits. Depressing. The economy paragraph does at least refer to brexit but it sees success as though economics were an olympic sport where London is defending its gold medal: making London as attractive as possible to the imagined global players, calling for an immigration system fostering access to talent and so on. There is a slightly surprising new (to me) strand of idiocy: that we need to protect our environment and our world class culture so that people and businesses around the world… A sentence about ensuring that everyone benefits and finally “I will also promote economic activity across London, day and night, and take account of the particular needs of small businesses operating in the capital.” We have clearly had no impact whatever: ‘across London’ reads to me like softening-up the reader for a throughly centralising plan in which suburban employment will continue to shrivel. And note that small businesses just have ‘needs’, no potentialities.

A portmanteau paragraph called environment, transport and public space then says nothing tangible though it does set a target for London to become zero-carbon by 2050. I must check whether that is significant, and whether it includes aviation. Nothing on reducing the need to travel. The final section of the summary returns to the overall title: a city for all Londoners and to me it seems excellent and relatively heartfelt. I just quote (most of) it: ‘For the city to be successful, Londoners in all their diversity must live well together. Social integration is a broad but vital concept – it means addressing inequalities, tackling disadvantage and discrimination and promoting full participation in the life of our city. It means considering how people from BAME, disabled, or LGBT+ communities, as well as women and young people from low-income families, are disproportionately affected by all issues in London – and making sure that in every area of policy, they are given the resources they need to make London a more equal city. Social integration relies on an affordable, accessible transport system, measures to improve health and reduce health inequality, and ensuring that the city’s amazing culture continues to thrive and unite us.…’

Nothing in this summary about democratic process except that that final paragraph on inequalities does have ‘…promoting full participation in the life of our city.’ [I’ll reflect and add more comments on that later. There are contradictory signs about City Hall’s attitudes to public participation this time round.]

There remains the unspoken issue of scope. The London Plan should deal comprehensively with the city but has always been blinkered by the fact that it has significance under the Town and Country Planning acts as part of the Development Plan and this has perhaps been a reason or a pretext for limiting it to land use and related transport issues, even though it is supposed to be embody the spatial integration of all the mayor’s strategies. (Check that wording). Thus the plan has nothing about the fiscal constraints on GLA activity or about the appalling and vindictive cuts which have been imposed by the Tories in national government on Labour Boroughs. It has nothing about health services despite the under-funding, privatisation and re-structuring being inflicted on them, nor about education or social security. The City Hall defence would be that health, social security and education are not competences of the GLA but that should not prevent their treatment in the analysis and the plan as essential to understanding the social and economic dynamics of the city (not to mention some severe coordination failures which flow from their omission).

Digression: the launch event

Some of us got seats (or just smuggled ourselves in) to the launch event this morning 31 October. There is quite a lot on Twitter #allLondoners, much of it from @Justspace7 but some from other people. A very middle-aged and mainly white crowd in the room.

The GLA fielded a powerful panel: John Lett + deputy mayors + Benson from Housing and others. The overall impact on me was that this is a slightly more encouraging apple pie than the apple pies of previous mayors but that everything depends on the detail of exactly how it is elaborated and implemented. All of the ideas and proposals, I think, were evident in officers’ discourse before the mayoral election, and many were embodied in the very undemocratic 2014 document London Infrastructure Plan 2050. If the new mayor has any hand in the new document it is a matter of emphasis: some modest proposals for private rentals and an aspiration for 50% affordable housing (though with much of it not in fact affordable to most Londoners). Pat Turnbull of London Tenants Federation and Just Space made the most powerful intervention from the floor, asking where were London’s working classes who had to make the greatest sacrifices —loss of their estates, displacement, seizure of their estate green space— to enable housing to be built which they could never afford to occupy. Applause. Richard Lee asked for audio and transcripts to be placed on the web site & was told that there would be written records of the workshops and launch (though probably not transcripts) but that audio would be given consideration…). Strong sense that ‘consultation’ is mainly by invitation. Delighted that the slides shown at the launch were made available the same day. I did, after the meeting, extract from Ben Johnson (advisor on business and digital policy) an undertaking to try and get a user-friendly PDF. End of digression.

Now to start reading the main sections…

Accommodating Growth

Starts by outlining population and household growth and the (unquestioned) need to accommodate it. There is a sentence in the first paragraph on the incursions that makes on the rest of the city’s land: “…As well as housing, it is also crucial to sustain and promote economic growth by making the right decisions about places of work. Land is in high demand for many other competing priorities, such as green space and infrastructure of all kinds.…” but still it is couched in terms of growth. It’s good to see it there but the devil is in the detail.

The discussion of land and floorspace for employment (I’d prefer to call it non-residential activity so it’s clear that it covers education, health, libraries and so on – but that sounds pompous) starts with central London —the Central Activities Zone CAZ— where the mayor plans to resist change of use from office to residential “…unless this can be justified…” and facilitate inward commuting.

In the rest of London the mayor says “Across the city, I will make provision for industrial and retail activity, and I will promote viable strategic locations for office space, including in Outer London.” This paragraph goes on with the assumption that fostering “regeneration” is an aim. A few comments on all this:

The text is trapped by some dead or dangerous categories: “office”, “retail”, “industrial” and “strategic”. First of all the range of activities which goes on is now really hard to force into the categories of land use classes. Vehicle repair takes place in all manner of premises; delivery/distribution of goods involves huge purpose-built sheds through smaller industrial estate buildings, retail ‘parks’ to tiny depôts, pickups and drop-boxes in shops, stations, petrol stations and so on. While the vehicle movements associated with all this distribution activity do seem to be alarming TfL, there is no sign that the premises dimension is getting any attention, nor that the pollution and congestion aspects are being examined. There is more to the economy and society than the property investors’ and planners’ categories of office, industrial and retail. The best passage in this text is the bit on cultural activities (“cultural capital’) where the full range of locations is reviewed. But the same could and should be done for the rest of the economy and that’s what’s missing. No sign here of the JustSpace discussions with GLA Economics about what they should be doing in their Evidence Base.

One of the fallacies embedded in London planning is that only very big things can be regarded as ‘strategic‘ and thus merit the GLA’s attention and policy: big industrial areas, big shopping centres. In fact major changes in the structure of London are the cumulative outcome of thousands of small changes, extinguishing services and jobs in high streets and behind them. This is what has led JustSpace to call for careful studies of these local economies.

We really do have to push for the GLA to start from the economy we have, paying as much attention to the non-sexy 50% of jobs outside the main centres and high-value sectors. They don’t seem to realise that the extinction of that activity makes a negative contribution to growth while improvements in pay, productivity and output there is just as much a contribution to growth as more jobs in finance and business services.

This chapter on conflicting demands for land breaks out inexplicably into a section on transport. It says “To manage this demand, I will look at introducing innovative methods, including using road space for different purposes at different times of the day, shifting lorry consolidation centres closer to the River Thames or the rail network, and encouraging more business deliveries by bike.” This all sounds decent, though the shifting of “lorry consolidation centres…” sounds half-baked, or perhaps a poor summary. perhaps it mean break-of-bulk rather than consolidation. Rail and river (and canals) are indeed good ways of bringing in heavy and bulky stuff, saving very large amounts of truck traffic. So thats good to see, but it means protecting wharves beside the water and keeping some railway sidings free of housing developments and that’s what we have to watch out for in the Plan, when it comes. Still nothing about reducing the need to travel by bringing homes and destinations closer to each other, fostering local services or realising the concept of ‘lifetime neighbourhoods’. [That was the only good idea to enter London Planning in the Johnson period and has now disappeared from the text.]