This blog post started as an abstract, put together in response to a plan by colleagues Susan Moore and Michael Short at the Bartlett in 2025 for a round table meeting on Critical Dialogues in Comparative Urbanism. The abstract was:

My enthusiasm for the project of dissolving disciplinary/professional boundaries in the Bartlett in the 1970s. Building student experiences to replace architecture, building and planning and knit a lot of ’science’ in the mix.

The highlights in my experience, notably the work of some individual students and the survival until [date] of the first year undergraduate module in which students studied the gestation of one London building and then took their methods on an overseas field trip

A research outcome in the Bartlett International Summer School on the Production of the built environment (BISS) which ran from 1979 to 1996, annual colloquium of scholars, trade unionists and a few activists built round an explicitly Marxist programme, leading to the International Network for Urban Research and Action INURA, founded in 1991 and still going strong as a network and annual meeting but never quite consummating its theoretical texts under the banner of The New Metropolitan Mainstream – though some of it appears in the work curated by Christian Schmid and Neil Brenner on Planetary Urbanism.

My personal effort from about 1990 to build BSP’s first new Masters programme European Property Development and Planning, initially parallelled by initiatives in Newcastle (Patsy Healey), Turin (Mazza, Ave), Venice (Folin) and … It struggled to become quorate for want of students with critical appetite but became a massive ’success’ as it later filled up with more business-oriented students from global elites and the newly capitalist countries. The international university partners faded away. UCL, BSP and many of the students got rich on the basis of what became IREP. A waste of 20 years, I think from my point of view.

Passages in red are bits I would like to mention in the round table session.

The UCL School of Environmental Studies

When I joined UCL as a lecturer in 1969 Richard Llewelyn-Davies was in the process of forming a new department with this title by merging the Bartlett School of Architecture, the Department of Town Planning and various research units. Part of the project was to break out of the blinkered framework of professions, enabling teaching and research to draw on urban history, engineering (his original discipline) and other social and physical sciences. There was no particular orientation to international comparative study in this programme but the staff body included eminent people from European traditions of the Architect-Engineer: Bruno Schlaffenburg, planning officer of the new borough of Camden, Walter Bor who had been planning officer of Liverpool together with Ruth Glass, sociologist from Berlin and Duccio Turin. I was an enthusiast for all this, having just spent some years in my first job in the master planning team for Milton Keynes which was great mix of ‘disciplines’ and boundary-crossing. I wrote about the stirring atmosphere of the 1970s (and its defeat by resurgent professions) in the festschrift for historian Adrian Forty: Yes, and we have no dentists (2014).

The 1970s did not, for me, generate ideas about critical comparative study but we already did international field trips – always to Bologna – so a lot of comparative work went on, albeit without much explicit analysis.

Research: BISS

Through the 1980s, as neo-liberalism was extending its reach and penetration everywhere, some of us were developing critiques in the Bartlett International Summer Schools on the Production of the Built Environment BISS. This was an annual gathering of more-or-less Marxist and radical researchers, trade unionists and professionals in which class relations in the production process were centre-stage. Much of the work was international-comparative in scope developing explicit Marxist framings for this. It was captured in a 1985 book edited by Michael Ball, myself and others and recently reprinted. For just one or two memorable years we ran a Bartlett MSc on Production of the Built Environment, using this material. [The annual proceedings of Biss have been scanned by Jake Arnfeld and are now online at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1QwqDhyeiothvxt_Z5GVDiWjNhBSy2vVV]

Some of these ideas were revisited in a teach-out on Rent in 2019 and a reading group in 2021. The production-focused research continued in the work at the University of Westminster where Dr Linda Clarke moved from the Bartlett.

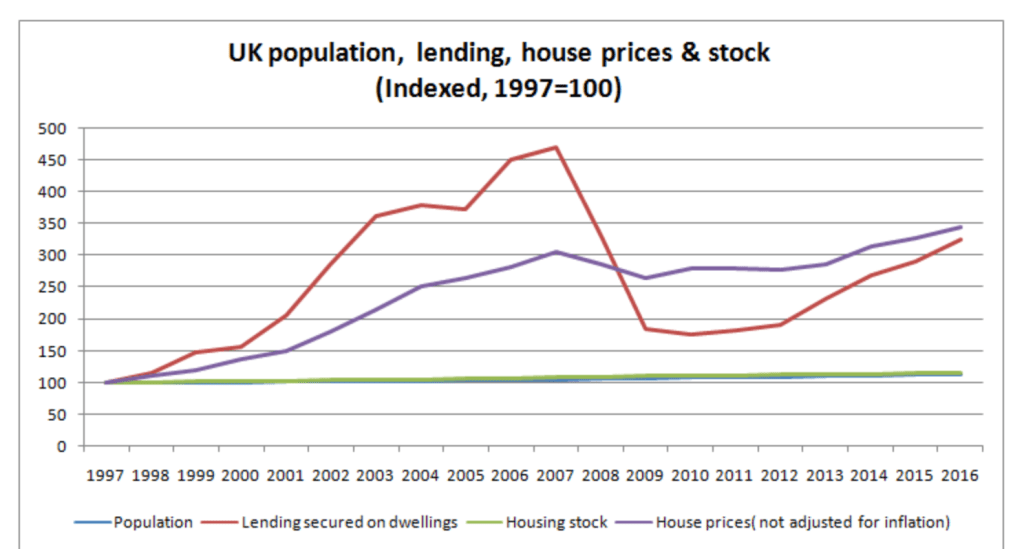

I was reflecting on this material recently when asked to write a chapter on a book which had influenced my teaching most. I chose David Harvey’s Urbanization of Capital and writing it helped me distill some clear principles of analysis. Rent theory à la Marx offers us powerful analysis of conditions under which rents of various kinds can be appropriated in capitalist society but is not a simple or blanket determination of what always happens. What actually happens is the outcome of underlying structural forces interacting with the particularities of landed property, tenure forms, tax regimes and so on in the place under study, and in the particular conjuncture being studied.

1990s: Roles and Relationships in the production of the built environment

The potentialities of international comparative study for teaching were most explicitly developed in a module which we ran through the 1990s, compulsory for all students in the Bartlett (now a faculty comprising departments with names like architecture, planning, construction). Fortunately it is well written up and preserved online though the journal in which it appeared is dead.

Reading it again is so refreshing. It was designed to engage new students in the analysis of London developments, looking at the interplay of finance, planning and other public policy, private capital(s), professions, unions, users. Working in groups, students covered the London Eye, More London, Barbican and so on. Finally the whole year went on a field trip to a foreign city where 3 days were spent trying to make sense of what we saw, without the use of documents or much language, simply learning to look, using the concepts developed in London. We didn’t call it critical comparative study, but it was.

Research: INURA

As the BISS was wilting in the 1990s ascendancy of neo-liberalism, we launched a new network in which activism was meant to be as important as research: The International Network of Urban Research and Action INURA. Like the BISS it was headquartered in Switzerland and has annual meetings, though without its own scholarly publication. Its ‘method’ consists of a few days of listening and exploring in a host city with local activists, interspersed and followed with informal workshops which engage with the research and theoretical interests of participants. An attempt at publication of a systematic study of multiple cities has foundered as the unruly crowd of contributors failed to meet the high ambitions of the main leaders, notably Christian Schmid. Under the banner of The New Metropolitan Mainstream, some of it appears in the work curated by Christian Schmid and Neil Brenner on Planetary Urbanism. Most of the work sits like an iceberg on hard drives around the world. It contains valuable attempts to define variables and episodes common to multiple cities and thus generate principles for critical comparative study.

EPDP

My personal effort from about 1990 to build BSP’s first new Masters programme European Property Development and Planning, was initially paralleled by initiatives in Newcastle (Patsy Healey), Turin (Mazza, Ave), Venice (Folin) and ?? It struggled to become quorate for want of students with critical appetite but became a massive ’success’ as it later filled up with more business-oriented students from global elites and the newly capitalist countries. The international university partners faded away. UCL, BSP and many of the students got rich on the basis of what became IREP. A waste of 20 years, I think from the point of view of developing critical comparative analysis.

I thought of adding instances of students, and student dissertations, which have represented the achievement of these aspirations over the years. F

Adesope, G. (1993) Public-private relations in two major station redevelopments MPhil, London UCL compared the King’s Cross railway lands with Paris Rive Gauche, both ‘regeneration’ schemes above and around major stations and both hit by the same crash of the speculative office markets. The thesis examined how the London project evaporated while in Paris the municipality just kept on building decking, running up mounting public debt but harnessed the new Biblioteque Nationale to occupy some of the space.

Reference list

Edwards, M, Campkin, B and Arbaci, S (2009) Exploring roles and relationships in the production of the built environment Centre for Education in the Built Environment (CEBE) Transactions 6, 1, 10.11120/tran.2009.06010038 http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/15579

Edwards, Michael (2014) “Yes, and We Have No Dentists.” In Forty Ways to Think About Architecture: architectural history and theory today, edited by Iain Borden, Murray Fraser and Barbara Penner, 280 pages. London: Wiley, ch 28, 2014. http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118822617.html

[ e-print Edwards for Forty ]

Ball M J, Bentivegna, V, Edwards, M, and Folin, M, Eds (2018) Land Rent, Housing and Urban Planning: a European Perspective Reprint of 1985 book in Routledge Revivals series. https://www.routledge.com/Land-Rent-Housing-and-Urban-Planning-A-European-Perspective/Ball-Edwards-Bentivegna-Folin/p/book/9781138494435

2022, Michael Edwards, Harvey’s Urbanization of Capital: why it helped me so much, in Camilla Perrone (ed) Critical Planning & Design: Roots, pathways, and frames, pre-print as accepted: edwards-on-harvey-v1 Book now published. Details and ordering at http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-93107-0…

BISS. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1QwqDhyeiothvxt_Z5GVDiWjNhBSy2vVV